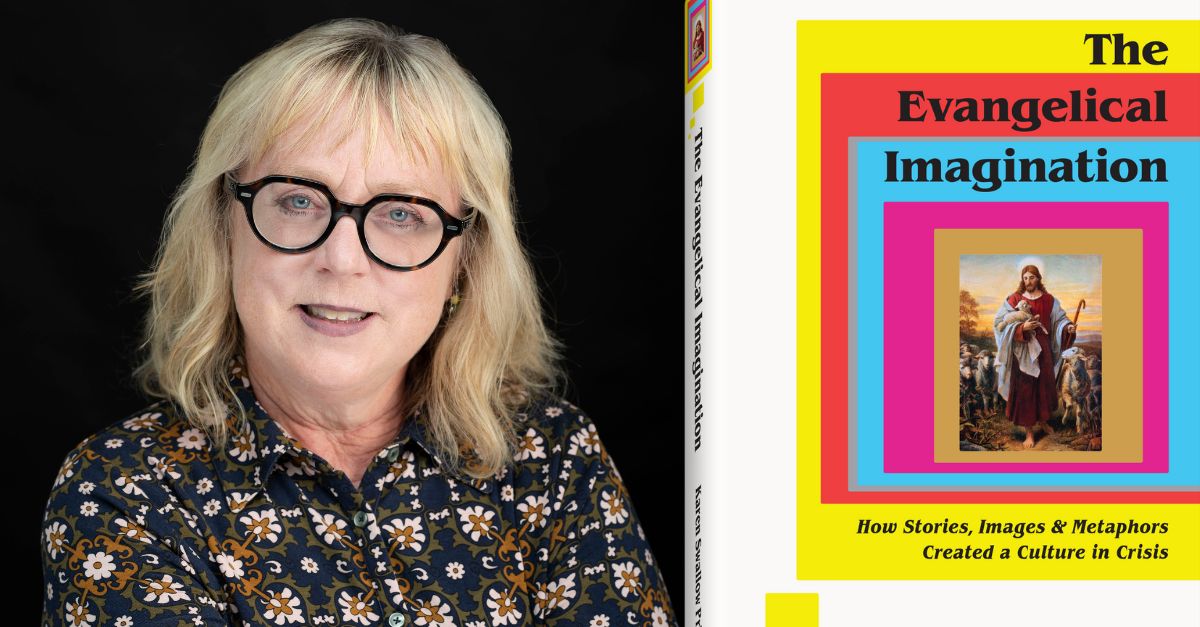

Karen Swallow Prior reads deeply and is passionate about showing Christians how good books can enrich their faith. Her work (listed in full below) includes the 2018 book On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books and articles published in places like Christianity Today, The Atlantic, First Things, and The Gospel Coalition.

In her latest book, The Evangelical Imagination: How Stories, Images, and Metaphors Created a Culture in Crisis, Prior makes an intriguing suggestion: we cannot understand how evangelicalism became what it is today unless we are willing to look at the past. In particular, we must look at the Victorian period, where the Great Awakenings laid the foundation for what we now call evangelical America.

Prior talks with G. Connor Salter about the book and how her past work informed it in surprising ways.

INTERVIEW

The term evangelicalism gets tossed around quite a lot. How did you define it within the book?

I offered a few definitions by well-respected scholars, but rely most heavily on the definition given by church historian David Bebbington, a definition known as the Bebbington Quadrilateral. Based on his study of the evangelical movement since its beginnings in the 18th century, Bebbington identifies four main emphases in the movement: an emphasis on the centrality of conversion to the Chrisitan life, an emphasis on the Bible as authoritative for the believer, an emphasis on Christ’s crucifixion for our salvation, and an emphasis on activism (such as witnessing, missions, and social reform).

Did any particular event or idea inspire you to write the book?

This book was in the making in my mind and heart for a long time. I’ve taught in evangelical contexts for over 30 years. The idea started from teaching Victorian literature and hearing a lot of my students observe that their experience in being raised evangelical reflected a lot about the Victorian culture of the nineteenth century. That was kind of fun at first, but it has come to pose a more serious a problem, as I see it, over the years. In the past decade or so, I’ve witnessed more and more young people raised in the American evangelical subculture needing to separate what is simply of that culture from the eternal and universal truths of the faith. That kind of distinction is one we always have to make as believers, or course. But it does seem in this particular historical moment that we’ve reached a crisis point (thus the word “crisis” in the book’s subtitle). I’m seeing too many people (of all ages) walk away from the church or even the faith because they feel like they were misled or even deceived.

Many writers discussing evangelicalism tend to start with the 1950s shift from fundamentalism to evangelicalism or perhaps the 1980s culture wars. You chose to take readers back further, back to the Victorian period. Why do you think we often miss the fact that evangelicalism has older roots?

Well, history is easy to forget (or to not even know). This is just general human nature, I think. (I have mainly learned history through the study of literature.) But in addition to that reality, within the American context, we naturally think primarily of American history. Even if we go back earlier in American history, as Americans, we likely think more about the Great Awakenings here than the Evangelical Revival of early 18th century England. But certainly, the most direct line to where we are in this moment within Evangelical America goes back to that fundamentalist/evangelical split. I think it’s helpful to go back even further.

Did the book connect to ideas you’d explored in previous books in ways you didn’t expect?

My biography of the 18th-century evangelical Hannah More (Fierce Convictions: The Extraordinary Life of Hannah More–Poet, Reformer Abolitionist), which was based on my Ph.D. dissertation, forms much of the foundation of my understanding of evangelical history. In a way, this new book journeyed back to my earlier research and writing to make the connections between that time and our own. It was my study of Hannah More that helped me long ago to understand that I am an evangelical and to embrace that. I still do. But this book helped me to see some of the bad fruit of that history that I hadn’t quite reckoned with.

You talk in chapter 2 about the need to understand “how Jesus, the Logos at the center of all creation, accommodates all human experience.” What are some things you’ve learned as you come to understand Jesus as the center of life?

As a lover of words, I’ve long relished the fact that Jesus is the Word, the Logos. I’ve also pondered often how Jesus as the Logos can be reflected in all that is logical and rational, including the entire order of the created world. But something I’ve been contemplating in more recent times is Jesus at the crux of it all–Jesus literally on the cross (which is the same word as crux) and Jesus metaphorically holding everything in tension in a perfect balance. He perfectly balances justice and mercy, the law and grace, humanity and divinity, this life and the one to come. Jesus at the center is the perfect embodiment of all that is both/and rather than either/or.

We often find that present problems are not as new as we think. For example, you note in chapter 3 that after the second Great Awakening, the next generation of Victorians went through a period of cynicism, “clearly foreshadowing today’s phenomena of deconstruction and deconversion.” What’s your reaction when you see the present resembles the past?

It actually gives me a lot more perspective—a little bit of despair but a lot of hope. The despair comes from wanting to say, “Look, we can learn from the past! We don’t have to make the same mistakes!” But the hope comes from the confirmation that there really is nothing new under the sun. People have gone through so much of what we have before (often worse!) and civilization and the church have survived. We may not learn as much as we might from the past, but we can hope that what we do learn in this moment will be something we can give to the future.

Chapter 6 deals with why so much Christian entertainment is kitschy—how too much sentimentalism makes bad art and isn’t good for us. However, you point out that the solution is balance: not too much sentimentalism, not too little. What tools have you found helpful for that? Do you alternate between reading serious and lighthearted books, or anything like that?

I absolutely do alternate between serious and lighthearted books. I mainly listen to suspense on Audible, for example. I do love Stephen King! I think half of the solution is in simply recognizing when a work of art or a cultural artifact is good or great and when it’s just something to soothe or entertain us. It’s all good–but a diet of one thing is never healthy. Candy is great, but not as our main source of sustenance. The parallel is true for all we consume.

You tell an interesting story in chapter 10 about talking with a young disillusioned evangelical and realizing that you’ve found it easier to keep the faith because you grew up before “the modern evangelical culture”—all the Christian subculture that has accumulated since the 80s. Any tips for disillusioned young evangelicals figuring out how they feel about the subculture they grew up in?

That’s a good question. It’s complicated because there are a couple of categories we need to consider. Some aspects of a subculture are good, of course, and many are just neutral. Others are harmful. I know a number of people who have been harmed–really harmed–by, for example, the distortions of purity culture. But when it comes to something like the cheesy, kitschy art of evangelicalism, I think it’s ok to both laugh and lament, recognizing, too, that these excesses and lacks aren’t unique to evangelicals or even to Christians. They are part of the human condition and all human culture. We will never escape culture this side of the new heaven and the new earth. Nor should we want to. We should simply desire and try to cultivate better cultures.

Chapter 9 discusses how evangelical leaders often approach ministry more like business professionals than shepherds. Any thoughts on how we can move toward a shepherding model?

Sometimes we can over-complicate things. All one has to do is decide to be a shepherd (rather than something else) and do it. I am sympathetic by nature to all the complications and tensions and nuances and competing impulses we all have in our various roles. But I am also tired of souls being sacrificed by sophisticated rationalizations. The Good Shepherd leaves the 99 to seek the 1. That’s what shepherds do.

You discuss End Times theology in the final chapter, noting that This Present Darkness and Left Behind both fit into a genre with a long history: prophecy fiction. Can you name some other prophecy fiction books that younger readers may not know about?

Hal Lindsey, whose book The Late Great Planet Earth I discuss, wrote a rapture novel called Blood Moon. Probably the most prolific writer of prophecy fiction these days is Joel Rosenberg. This is an area completely outside my expertise. Crawford Gribben’s Writing the Rapture: Prophecy Fiction in Evangelical America is the best source I know on this topic.

You talk in chapter 10 about how the church must always be reforming and how evangelicals currently need to reform by considering their credibility. Any thoughts on first steps that evangelicals can take in that direction?

A friend of mine describes what we are going through now in this painful time of division and revelation as the “great sort.” As culture and Christianity get more and more entangled, it will, ironically, become clearer and clearer who truly believes the Christian faith and follows Jesus–and who is after something else. As Russell Moore has observed, “We now see young evangelicals walking away from evangelicalism not because they do not believe what the church teaches, but because they believe the church itself does not believe what the church teaches.” It seems like every day we are facing forks in the road between culture and Christ. Take heart that we are all in this “great sort” together. Take courage and choose Christ in those moments, every day.

I know you’ve recently started a substack, The Priory. Are there any other ways you’d encourage readers to check out your work—regular columns, that kind of thing?

I’m turning most of my attention now to The Priory. But I also write regularly as an opinion columnist at Religion News Service. But, mostly, I’d love people to read my books. You can check them out at my website, karenswallowprior.com.

Karen Swallow Prior, Ph. D., is a reader, writer, and professor. She is the author of The Evangelical Imagination: How Stories, Images, and Metaphors Created a Culture in Crisis (Brazos, 2023); On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books (Brazos 2018); Fierce Convictions: The Extraordinary Life of Hannah More—Poet, Reformer, Abolitionist (Thomas Nelson, 2014); and Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me (T. S. Poetry Press, 2012). She is co-editor of Cultural Engagement: A Crash Course in Contemporary Issues (Zondervan 2019) and has contributed to numerous other books. She has a monthly column for Religion News Service. Her writing has appeared at Christianity Today, New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, First Things, Vox, Think Christian, The Gospel Coalition, and various other places. She hosted the podcast Jane and Jesus. She is a Contributing Editor for Comment, a founding member of The Pelican Project, a Senior Fellow at the Trinity Forum, and a Senior Fellow at the L. Russ Bush Center for Faith and Culture. She and her husband live on a 100-year-old homestead in central Virginia with dogs, chickens, and lots of books.

Cover photo credit: © Getty Images/akkachai thothubthai